Biologically speaking, orienting is a novelty seeking response that helps protect us from threat and point us toward new resources (Pavlov 1927 cited in Ogden 2006). It is also a critical point of reference in trauma healing modalities like Somatic Experiencing and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. In a therapeutic context, it’s used as one of the first steps in establishing environmental and relational safety that resonates on a deep biological level (Levine 2010). You might even say that the impulse to orient resonates across evolutionary time, because it is a basic behavior that we hold in common with all lifeforms. So what if we embraced orienting as a frame for interspecies belonging? My arrival at this premise demonstrates our uniquely human ability to orient towards large, abstract concepts. Because the human brain has a talent for representing complex ideas through storytelling, it is also possible to think of orienting as something we do towards imagined realities.

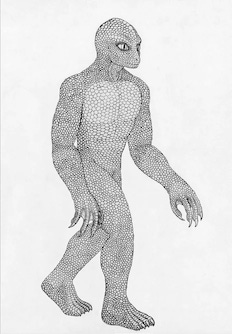

At the moment, the uniqueness of the human brain seems to be oriented towards not so unique practices, like resource hoarding and dominance behavior. Sometimes it seems like we’re a failed evolutionary experiment. But other times, the expressive qualities of human beings yield novel forms of collective inspiration. In those inspired moments, control structures give way to the spontaneous, liberatory impulse towards creativity and self-organization. From the perspective of Polyvagal Theory and Interpersonal Neurobiology, our aptitude for complex social co-ordination is newer in evolutionary time, but utterly foundational to our experience of being human (Schore 2007, Porges 2021, Chan 2021). When it comes to the predictable dominance behaviors, I see lizard people who won’t surrender the wheel.

The challenge with dispossessing the lizard brains of the wealth they have stolen is that they do something simple very well. The complexity of developing empathy for diverse experiences within reciprocal relationships is irrelevant to their simple ruleset of accumulation at all costs. The embrace of multiplicity may not be simple, but it is the basis of life and the precious substance of relationships. Now for a big question: what if those of us who want to build a world oriented towards multiplicity have to suspend our ideological differences? What if orienting could be a functional alternative to the divisive pitfalls of ideology? I am orienting towards humility, connection with the earth, and the subversive power of embodied relationships, what about you? There’s a lot of room to experiment. It’s not a ruleset, it leaves room for surprising resonance and refinement without the total loss of coordination that comes from the inevitable dissolution of any rigidly held ideology. It is autonomy in coordination. Without a name it can’t be undermined. It’s simply something we’re doing. The story tells itself through the process of living. We SENSE our belonging, we FEEL it. The participation of our abstract minds is recruited simply to recognize that this is something we’re actively CHOOSING. And the ability to choose beyond immediate survival is a freedom made possible by our status as a complex social organism. It is the possibility to find safety as a group without ideology, based on trust in a shared humanity (unless you’re a lizard person).

Biologically speaking, you orient in order to decide whether to move towards or away from something. For example, you could say anarchists orient towards mutuality and away from hierarchy, or you could say they orient towards a set of confrontational practices that seek to undermine state power. You could also say, in the spirit of David Graeber, that someone might orient towards anarchy without even realizing it. If you orient towards common decency of your own free will, if you orient towards consensus without the use of threats, if you orient towards sharing power, you may be an anarchist.

In Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, trauma therapist Pat Ogden makes a distinction between covert and overt orienting. Overt orienting is external and prompts a behavioral response, whereas covert orienting is internal and prompts a physiological response. Trauma can move these out of alignment, and the work of recovery involves noticing when this is happening and allowing the possibility for safety in the present moment to be a bridge. Ogden writes:

“Because the act of orienting is “fundamental to human learning and cognitive functioning,” changing trauma-related maladaptive orienting tendencies is essential to successful treatment (Kimmel, Van Olst, & Orlebeke, 1979)” (Ogden 84).

With respect to a wide range of personal and collective experiences of trauma, I wouldn’t be the first to suggest that we live in a traumatized culture in general (Menakin 2017). Perhaps we share, with a great diversity of presentations and severity, some “trauma-related maladaptive orienting tendencies” in response to the naturalization of victim blaming and systemic inequality.

What if our accumulated orienting behaviors could lead to a collective act of refusal with a true diversity of tactics? What revolutionary surprises would emerge if the lucky ones oriented to their 10,0000 hours of healing in therapy as a public good? What if this was a choice we made without giving up on our individual longings? What if we became aware that any time we’re not doing that we’re orienting toward something else? As philosopher Bayo Akomolafe and many others have said, the body is a process, and we are always in practice. There is no quick fix mindset to differentiating from the toxic environment of the United States. It is a slow and embodied divestment that can only succeed alongside a growing reflection of the world we want in our relationships. In generative somatics, a somatic methodology created by activists and organizers, extricating our soma from the subtle, and not so subtle forces of coercion is the building block of effective collective action.

Ogden writes:

“What we turn our attention to, or orient to, determines not only our physical actions but our mental actions as well. We sustain a preparation to orient at all times, during sleep as well as during wakefulness (Sokolov, Spinks, Naatanen, & Heikki, 2002), and this preparation is both physical and psychological” (Ogden 84).

Orienting is a subtle compass but a constant one. If we continue tuning it towards mutual understanding, little by little we may find ourselves on the path to an embodied sense of collective safety. When we do this, I imagine the revolutionary longing to belong through reciprocity and service will organically return as if that’s what we were meant to orient towards to all along.

Reference:

Chan, A. (2021) Reassembling Models of Reality: Theory and Clinical Practice. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Ogden, P., & Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands. Central Recovery Press.

Porges, S. (2021). Polyvagal Theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100069

Schore, J.R., & Schore, A. (2007) Modern Attachment Theory: The Central Role of Affect Regulation in Development and Treatment. Clin Soc Work J 36, 9–20 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0111-7